Telling stories has power; they connect us, help us work through the raw emotion, and give us a way to make sense of events. After last week's devastating violence in Paris and Beirut, these nine bloggers shared theirs, helping us do just that. Reading their posts may not be easy -- but it is important.

A writer from Cultive le Web was out for an evening with friends Friday night when shooting began on the rue de Charonne. The staccato phrasing of this play-by-play post captures brings readers some tiny measure of the fear, panic, and disbelief. It's an unvarnished outpouring we wish he had no occasion to write, but are glad he did.

9:45 p.m. Noise, screams. A fight? A rowdy crowd there at the bar? They must be drunk, like on any Friday night in Paris, right? I come closer. A group of people has formed on the other side of the sidewalk. "Kalashnikov shots." "Casualties." "Dozens of casualties." "Broken glass, everywhere." There's a gush of details -- who to believe? What to make out of this? What are they talking about? A shoot-out? Settling scores like in Marseille? But thinking about it, why not a terrorist attack? I ask, naively. "Obviously it's a terrorist attack!" answer the patrons who'd fled running, all at once.*

*Translated from the French by WordPress.com editor Ben Huberman.

Patrick lives in Paris' 11e arrondissement, a short walk from Le Bataclan. Waking up the morning after Friday's attacks, he looks for patterns in the violence that might give him hints for staying safe -- but finds none.

It makes sense, sadly, that an attack may occur at or near a French football match – the President was there, after all. We can avoid large displays of nationalism, sports, culture or otherwise. But must we also avoid all American rock bands? Was it something about the name Eagles of Death Metal? Do we stay inside on Friday the 13th? Never patronise Cambodian restaurants? How long is a piece of string?

Paris isn't the only city in mourning; bombings in Beirut last week left over 40 people dead. Lebanese blogger Joey reflects on the lack of global attention on Lebanon, with sense of resignation tempered by the hope that we can do better.

'We' don't get a safe button on Facebook. 'We' don't get late night statements from the most powerful men and women alive and millions of online users.

'We' don't change policies which will affect the lives of countless innocent refugees.

This could not be clearer.

I say this with no resentment whatsoever, just sadness.

On A Separate State of Mind, Elie reacts with more anger than resignation -- anger at the world for caring more about Paris, but also at his countrymen and women for seeming to do the same.

We can ask for the world to think Beirut is as important as Paris, or for Facebook to add a "safety check" button for us to use daily, or for people to care about us. But the truth of the matter is, we are a people that doesn't care about itself. We call it habituation, but it's really not. We call it the new normal, but if this [is] normality then let it go to hell.

In the world that doesn't care about Arab lives, Arabs lead the front lines.

Video game blogger Drew turned to more serious topics after the attacks on Paris, penning a thought-provoking post on whether being "united" against terror is a laudable goal, or a positive idea at all.

It's a sobering (and, it must be said, fundamentally French) thought: That the people killed in Paris "had declared war" on terrorism not because they imagined themselves conscripted into a fighting force, and certainly not because they marched in cultural and rhetorical lockstep, but specifically because they weren't in lockstep. They were living out the messier, more joyful, less "united" way of life that terrorism seeks to undermine...

We don't have to be united. We don't have to agree. We don't always have to "stand together," even. That's precisely what makes us strong, and that's precisely what makes our way of life worth defending.

John Scalzi, "Paris"

Author John Scalzi also veered from his regular bailiwick, science-fiction. His short but impassioned piece exhorts us to avoid giving credence to the Islamic State's black-and-white worldview by refusing to conflate "Muslim" and "terrorist."

Don't do what ISIS wants you to do. Don't be who ISIS wants you to be, and to be to Muslims. Be smarter than they want you to be. All it takes is for you to imagine the average Muslim to be like you, than to be like ISIS. If you can do that, you make a better world, and a more difficult one for groups like ISIS to exist in.

Analyses of tragic situations are quickly followed by calls to stop politicizing tragedy -- i.e., to stop analyzing at all, and allow people space to grieve. Idiot Joy Showland's Sam Kriss rejects that request, explaining why in this cogent piece.

When it's deployed honestly, the command to not politicise means to not make someone's death about something else: it's not about the issue you've always cared about; it's not about you. To do this is one type of politics. But there's another. Insisting on the humanity of the victims is also a political act, and as tragedy is spun into civilisational conflict or an excuse to victimise those who are already victims, it's a very necessary one.

Natalia's poem was written well before last week's events but published this week, a fitting tribute to the city of love.

In Paris they ask the right questions:

"Cognac, armagnac, or calvados?"

And, "Why are your eyes so blue?"

"Do you know how to get back home?"

"Is it finally time to kiss you?"

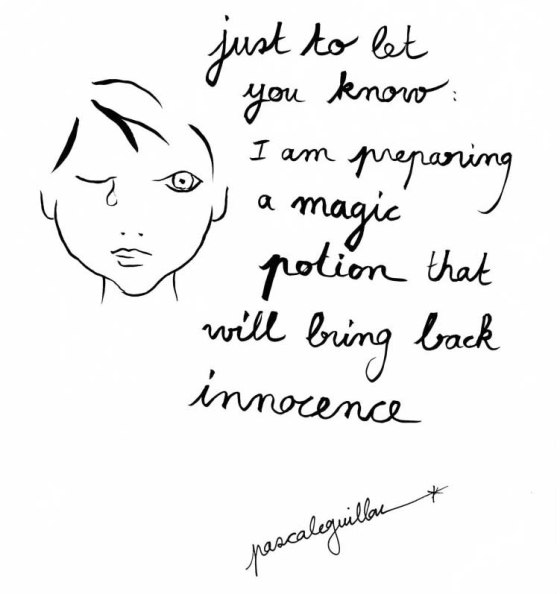

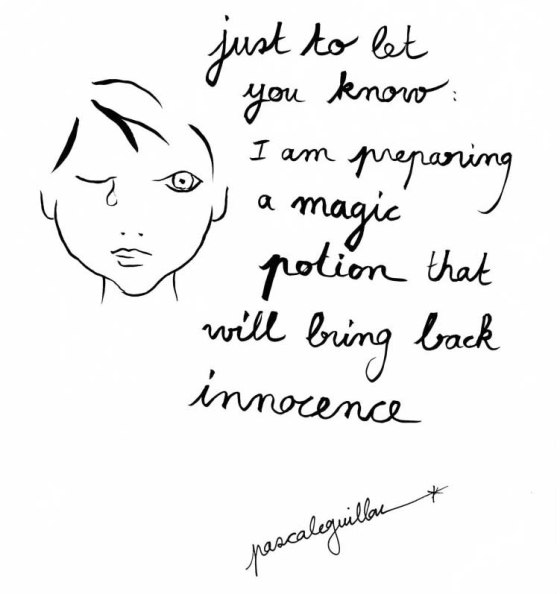

Illustrator Pascale, a Frenchwoman living in the Netherlands, reacted with pen and ink. Her lines are simple but heartbreaking, reminding us of something we all want but can't have -- whether we're in France, Lebanon, or anywhere else.

Please feel free to share the posts that moved you and made you think in the comments.

0 comments:

Posting Komentar